Here are a few photos from yesterday’s evening with Paulo Panico. (As usual, I am not in any of the photos as I was behind the camera)

Thank you Paulo for giving us your time and for a fantastic update on STEP.

Welcome to the website of James Turnbull TEP LLB., independent family succession adviser

Here are a few photos from yesterday’s evening with Paulo Panico. (As usual, I am not in any of the photos as I was behind the camera)

Thank you Paulo for giving us your time and for a fantastic update on STEP.

I am delighted to be presenting again at this conference organised by the Czech Bar Association, STEP and the APRSF.

The conference takes place on 4 November and you can find details here.

I am delighted to be presenting at a seminar on using trusts for business purposes which will be held on 8 November.

In the Czech context, this is a fascinating topic. So far in CZ, trusts have been used almost exclusively to achieve family rather than business objectives. However, I have already had the privilege of being involved in a small number of very successful Czech business structures using trusts. They highlight a terrific opportunity.

Czech commercial lawyers have a set of tools to solve problems which were developed in ‘pre-trust’ history. They know how to use those tools, and those tools usually work (more or less). As a result, they are not always open to new solutions – even when those new solutions are better than the old ones. It is also true that Czech law and Czech tax law can make using trusts challenging and that is sometimes used as an excuse to dismiss the idea completely. However in reality it is possible to overcome many of these so-called problems.

My part of the seminar will look at how trusts are used internationally to achieve business objectives. For each objective I will explore in detail at how it works internationally and then, together with participants, brainstorm how it could work here. (Spoiler – some things do not work, some other things work really well). Because this is unexplored territory, I do not promise to provide every answer. I do promise to provide plenty of food for thought!

More details of the seminar – plus the registration link – are here.

Here’s another in my series of ‘Answers to Questions People ask me”

This month’s question is “What is a Family Office?”

While this sounds like an easy one, it’s not. Over the last decade ‘family office’ has emerged as a buzz-phrase. Wherever you look, you see family offices where before there were none. But these words describe all manner of different things. Many of these things are excellent. Some are not. This article will therefore serve not just as an educational tool, but also as a consumer warning about some traps to avoid.

Wealthy families always have a team of experts to help them manage their wealth. Who exactly is on the team will depend a lot on the nature of the family and the kind of assets they own. The team is almost always going to include a lawyer and an accountant or tax adviser. Other members of the team can include investment management specialists, portfolio managers, real estate managers, estate and farm managers, trust and foundation specialists, family succession experts, and others including business advisers, art specialists and so on.

The starting point is that these activities are outsourced to third parties, and someone in the family (usually the founder of the family business) is responsible for managing this panel of experts and calling them in, as required, to solve problems.

But after a while, as family wealth grows, this fragmented outsourcing approach can stop making sense because:

When these things start to happen, a family office makes sense.

In this context, a family office means bringing some or even all of these external advisers in-house, under the control and supervision of a manager or coordinator of some sort. At a certain point, doing it this way not only improves efficiency but can also actually reduce cost. Another plus is the elimination of conflict of interest. Family office professionals do not work for other families or for external firms. Instead, they are focused exclusively on your family’s wealth and your family’s success.

For the aristocracy, the family office concept is not new. For centuries, noble families have had Estate Managers and Estate Offices – primarily to look after family land holdings. It is a very natural step for these to evolve from Estate Offices to Family Offices, still looking after the family land, but now also their wealth. The Duchy of Lancaster is a great example of this. Established in 1351, it does not describe itself as a family office – but that is exactly what it is.

The smallest family offices consist of a single person managing wealth on behalf of a single family under the legal umbrella of a company, or sometimes a trust or foundation. In this case, the single person (let’s call her the CEO) is still managing most of the team of outsourced experts we talked about above, but she is probably performing some of the most important functions herself. She is also keeping everyone focused on the family goals and strategy and making the founder’s life much simpler by taking most of the hassle off his hands. This model is sometimes a beginning point from which things will develop in the future as family wealth grows.

A more typical size for a small family office would be around five people, and then it goes upwards from there. In some of the largest family offices, you will see a team of 50 employees or more. As well as these professional staff, you will also find support staff – drivers, security specialists (bodyguards), personal assistants, and yacht crew. In this model, the family office is not just looking after the family wealth, it’s looking after everything.

So we see that there is no ‘one size fits all’ solution. Much depends on the nature and internal expertise of your family, and much also depends on the nature of your family’s wealth. For example, a passive investment portfolio requires less intensive focus than an active portfolio of start-ups, venture capital, or real estate development. These things dictate not only the size of the family office, but also who exactly the professional staff will be. But above all, each of those people is focused on the family strategy and goals.

Family office structures also allow you to focus capital on the industries from which you made your wealth. If you can truly understand something, you are far more likely to succeed. Finally, family office structures allow you to fully embrace the environmental, social, and philanthropic themes that are important to your family.

So every family office is different – but there is one important feature they (should) all share. Family offices are not profit centres. Yes, they are all about managing, protecting, and growing family wealth, but they themselves are not ‘for-profit’ business ventures. Instead, they are cost centres. Running a family office costs money. For some families that’s a worthwhile cost. For others, not.

If you think a family office might make sense for your family the first question is whether the cost, as we discuss above, is justified by the potential benefits.

As a rule of thumb, many people recommend that the ‘trigger point’ for establishing a family office is a family wealth of around EUR 100 million. At that point, the cost of a smaller family office (cca. EUR 1 million per annum) starts to make sense, given the relative savings in professional and other fees.

My feeling is that in the CEE region because our costs are lower, the target number is closer to EUR 40 million.

Of course, once family wealth grows to bigger numbers, then justification of the cost vs benefit equation is less and less challenging. Jeff Bezos’ family office, Bezos Expeditions, is the largest in the US. It manages assets of USD 100 billion, so a few extra million spent here or there on the 159 employees is relatively trivial.

There is another model that is relatively popular; the Multi-family Office (MFO).

As the name suggests, a MFO is a family office that looks after two or more families rather than one, and is often presented as a ‘stepping stone’ towards a standalone single-family office. In its purest sense, it is a true ‘cooperative’ between the families involved and follows the same ‘cost centre’ financial model as a single-family office.

A MFO can sometimes make sense, especially if the families involved are close to each other and/or very similar in terms of their objectives and goals. Doing it this way has some advantages. It lowers the cost threshold, and to some extent allows sharing of expertise and skills. It can also allow families to access bigger teams with a wider range of skills and experience. By pooling financial resources MFOs can also sometimes open doors that might otherwise be closed to individual families.

On the other hand, a MFO system also dilutes some of the family office benefits we outlined above – especially the purity of focus specifically on your family goals. The more families there are in the MFO, the more the benefits dilute. MFOs with two or three families can work really well. Anything above five is quite challenging.

So yes, a well-thought-out MFO structure can work really well for some families. But beware . .

Over the last decade, many wealth management companies and financial advisers have seized on the buzz surrounding the family office concept and rebranded themselves (or a part of their business) as “XYZ Multi Family Office”. In doing this they hope to emphasise their claims to provide a comprehensive set of professional solutions in-house or at least in a coordinated way.

Despite this branding, these companies are not true family offices in the sense described above. They are not run by the families, for the benefit of the families. Instead, they are business entities owned by others. That’s not necessarily a problem, but it is a reason to be cautious and aware:

Having said that, there are also some excellent commercial multi-family offices out there offering professional and capable service. In the Czech context, good examples include J&T Family Office and Emun. Wherever you go, caveat emptor – do your homework before you commit.

If you think setting up your own family office might make sense, the first step is to define your and your family’s goals – both in the short term and also over the longer term. A family office structure can often be a part of a wider family succession strategy – creating a structure to manage family wealth for not just this, but also for future generations.

Before you decide on the type and scope of your new family office, it is obviously important to prepare a budget. You can then consider if the concept makes sense financially for your family and if necessary, how to tailor it so that it does.

Once you have set your goals, creating a family office is similar to establishing any other business entity. I am also happy to help you with this. Please feel free to contact me if you would like any guidance or assistance in this area.

As part of my consulting business, I seem to end up doing a lot of tailor-made training – not just in the area of trusts and foundations, but also in business and family succession strategies and planning.

I am happy about that as I really enjoy training.

Because there seems to be the demand, I have added a dedicated section on my website and look forward to even more training projects in the future.

For more information see my new dedicated Training page.

Here are a few photos from this evening’s event at which it was a pleasure to welcome Dimitar Hristov who heads the Tax practice at DLA Piper’s Vienna office.

I also spoke briefly about possible cooperation with STEP which we will explore more fully in October

Dimitar’s presentation was fantastic and opened a few eyes to Austria as a jurisdiction.

It was great to see the friends who came to our book (re) launch. We tried to invite all the people who have helped us over the years.

Thanks also to the super team at Champagneria. Unlike many venues, they don’t get upset when you deliberately pour your drinks on the floor!

For most families, establishing a trust is an important decision. Quite a lot of money can be involved, and you will be stuck with the results of your decision for a long time. In this way, trusts are like cars. Buying a car is also a relatively big decision and you are also have to live with the results of your decision.

But that is where the similarity ends.

You can see a car and you can touch it

When you go shopping for a car, you can look at the car in the showroom, you can sit in it, and you can feel the quality of the interior. You can close the door and listen to hear if you get a “clunk” or a “clink”. Looking at the car, even before you take it for a test drive, you can form some opinions about whether you like it and whether it is the right car for your family. Is it big enough? Is it too big? Is it strong enough? Is it comfortable enough? Is it practical?

Sometimes it is easy to recognise that a particular model is not suitable for you.

Caption: This one is very economical but not the ideal family car

In contrast, all trusts look like this:

The good ones look like this, the bad ones, the deluxe ones and even the ones that don’t work at all, they all look like this.

The price of cars correlates (at least to some extent) to their quality

People understand that as a general rule, better cars are more expensive. Thus, a Skoda Superb costs more than an Octavia, which in turn costs more than a Fabia.

Based on my experience, this rule doesn’t apply to trusts. It is true that a very ‘cheap’ trust is more likely to be a bad one but spending a lot of money is also no guarantee of quality. Some of the worst trusts I have seen have also been some of the most expensive.

Most people understand at least something about cars.

You don’t have to be a mechanic or a motoring expert to recognise some basic issues that a car might have. For example, if your car is missing wheels, or some other fundamental part which will prevent it from working, you won’t buy it. If the car has bad rust it might fall apart. You can see that and so you won’t buy the car. And if your car isn’t working, then you know it isn’t.

Sadly there are many people out there who have trusts that simply don’t work. They are missing the legal equivalent of wheels, brakes, or steering. But because of the nature of trusts those same people don’t even realise that they have a problem, and by the time they do realise, it is too late.

Some of these ‘bad trusts’ are so bad that they are far worse than having no trust at all.

You can take a car for a test drive

With a car, you can try before you buy. With a trust there is no way of doing that. As I said above the only real way to ‘road test’ your trust is to wait for something to go wrong and then see what happens. But of course, by then, it’s too late!

Optional Extras cost more.

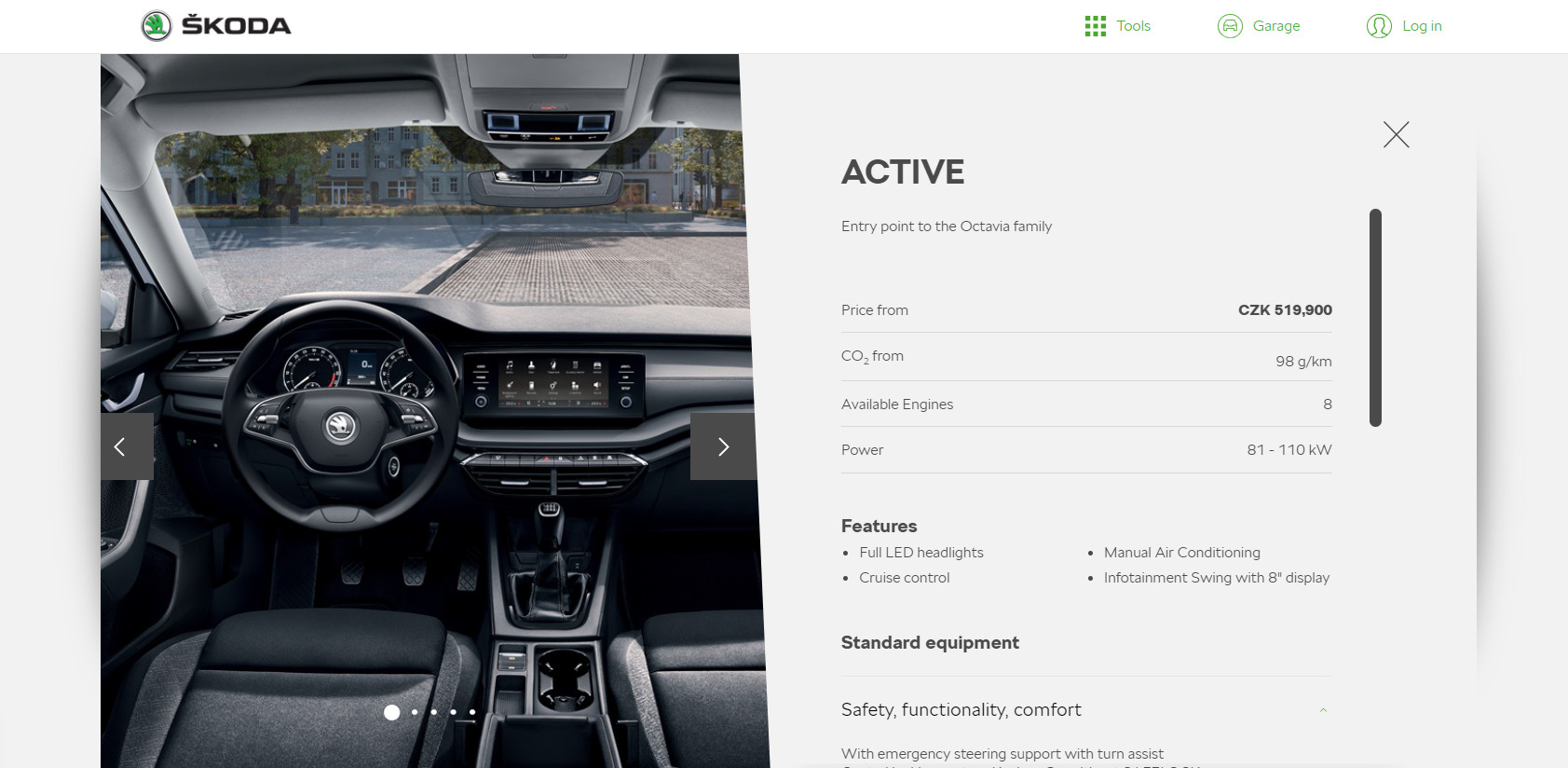

With a car, there is a base price. For example here is the entry-level Skoda Octavia:

With most new cars it is possible to add ‘optional extras’ for some additional cost.

This Octavia includes a lot of features that are not optional at all (wheels, seats, steering, brakes, windows etc). But the standard model also includes quite a few things that are not really essential, but nice to have. For example, air conditioning, cruise control, and central locking. Skoda considers these as standard features, which are included automatically in the price: 519,000 CZK (21,000 EUR).

But if you want, you can play with the configurator on the Skoda website and add a few optional features. I did that. I chose a different engine, metallic paint, a towbar, heated seats and so on. In no time my price increased to 731,000 CZK (29,600 EUR).

Do I really need these extras? Perhaps I don’t. But even so, they would all certainly be nice to have.

For example, I don’t plan to tow a trailer, but who knows? One day, having a towbar might be useful. On the other hand, is it worth the extra 25,000 CZK (1,000 EUR) for something I might never use? Perhaps not.

Trusts are a bit different.

For example, your trust documents could include the possibility for you to make changes to your trust, the ability for the trustees to borrow money or to own cybercurrency. They could include the possibility for you to appoint a supervisor. They could include the possibility for you to relocate the trust to a different country.

Many people really don’t need these extra things just as I don’t really need a towbar. It is very important to point out that you cannot do these things unless your trust has clauses that allow them – just as I cannot tow a trailer if I don’t have a towbar.

But unlike the towbar, the ‘optional extras’ for your trust are normally free. They are not pieces of metal but rather (standard) words printed on paper. It may be that you have no plan to buy bitcoin or appoint a supervisor, just as I have no plan to tow a trailer. But because there is no additional cost, the basic starting point for good trust should always include:

Of course once you start to ask for truly unique features (a jacuzzi built into the back seat, machine gun mounts) then those things will need to be tailor-made for you, and that will, of course, cost more. Likewise, if your trust is not standard (not a car at all but rather a bus, a truck, or a tank) then different rules will apply.

But I see too many people paying the deluxe price for a basic car, and sometimes they don’t even get all the essential standard features – let alone the full set of optional extras.

Goodness! This is complicated. What should I do?

We have some simple tips to help you avoid these pitfalls:

If you would like a second opinion of your proposed or existing trust, please contact me. Together with truly experienced legal experts I can make sure your trust includes all the optional extras and is really delivering value for money.

Here are a few photos from yesterday’s excellent APRSF event at which I spoke briefly.

There are no photos of me in this collection because I am the one holding the camera.

It was nice to learn that the first edition of our book, Svěřenské fondy – krok za krokem, was successful; so successful it seems that it has sold out.

Next week we expect the second edition to arrive from the printers

Many ordinary Czech people know something about trusts, and are increasingly interested in knowing more. They are interested not just in how trusts can help the wealthy, but also how they can help their own families.

Many ordinary Czech people know something about trusts, and are increasingly interested in knowing more. They are interested not just in how trusts can help the wealthy, but also how they can help their own families.

Before we published the first edition of our book there was no easily accessible source of this information.

Our book is aimed at these ordinary Czech people and is written in language that they can understand. It is not dry and boring, but rather as fun and entertaining as possible. It provides practical rather than theoretical information.

The second edition is also updated with the latest information on the Register of Beneficial Ownership and includes two new chapters.

If you would like to order a copy of the second edition, please contact me. The book costs 379 CZK plus 49 CZ postage and handling (a total of 428 Czech Crowns).